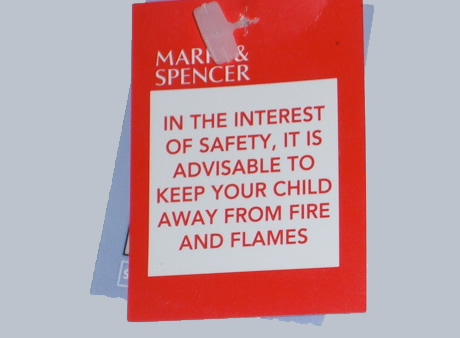

Awaiting a fiery reaction from the St Michaels (Gove and Wilshaw, that is)

COMMENT – Have you noticed how most educational research, conducted by seemingly elite bodies and organisations, has a tendency to culminate in what Basil Fawlty would have described as a ‘statement of the bleedin’ obvious’? This was the very phrase which immediately sprang to mind when I read an article in the Telegraph of 11th September 2012, describing how research by the OECD showed that the ‘The UK’s school system is socially segregated, with immigrant children clustered in disadvantaged schools.’

Picking myself up from the ground to which I had collapsed in complete and utter shocked amazement, you can only imagine how astonished I was on reading further that the OECD had declared that this bit of research also showed that ‘the socio-economic make-up of the UK’s schools poses “significant challenges” for immigrant students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds.’

I wonder how they conducted this particular piece of ground-breaking research? Perhaps they popped into the pub nearest to a school serving one of our most deprived areas – let’s call it the Jeremy Kyle community college – at the end of last term and asked the beleaguered teaching staff whether or not they felt significantly challenged by their pupils. The researcher would, of course, have had to wait until the staff had unrolled their eyes before hearing them all declare ‘No! Every day is like teaching in fairyland. Even those children who live in houses where no-one’s ever worked and they’re only spoken to about once a fortnight arrive at school each day so ready and eager to learn it makes your heart swell.’

The researchers might then also have covered a school in an area where large numbers of immigrants from third world countries live – let’s call it Babel Academy. Perhaps they did a vox pop at the school gates, waiting hours for each exhausted teacher to emerge, blinking, into daylight from their ‘Building schools for the future’, artificially-lit buildings. And the questions asked might have included such gems as ‘What do you reckon – is it a little bit harder teaching in this place, where almost every child speaks English as their second language, where few have parents who speak much English and many of those parents are functionally illiterate in their mother tongue as well as English?’ If any of them had any strength left after spending all day, every day hurtling around their classrooms trying to assist large groups of children with the widest possible range of educational and linguistic needs, they might have aimed a feeble punch at their inquisitors.

I know what it’s like, because I taught for the first fifteen years of my career in four, extremely different London schools. The first was a good, ethnically varied all boys school in West London and so when I moved on to a school near Brick Lane, I could have been forgiven if I’d thought ‘A school full of nice Bangladeshi boys – they’ll be well behaved and studious, just like those middle class boys of Asian descent I’ve recently been teaching.’ The difference between the two experiences couldn’t have been greater and I’d got more than five years of teaching under my belt at this point – and league tables, targets and pressure beyond anyone’s wildest imagination were still on the DfE drawing board. It took me the whole of my first term to get over the shock of how many boys in each class I taught couldn’t speak English at all, as many were only recent immigrants to the UK, yet I was expected to teach them to GCSE level in the same class as a few boys who had been born in the UK and were completely bilingual. Many of the children at the school lived in squalor that had to be seen to be believed; accompanying pastoral colleagues on home visits sometimes brought me to tears, especially when parents would force us to sit and take food with them.

We’ve been here before, however. It will be only a matter of time – and I’ll bet that the usual suspect (naming no names, but he’s called Michael, is the secretary of state for education and has A level Smuggery) is preparing his ‘No excuses…children are being failed by crap teachers…the state sector must learn from the excellence of the private…etc’ speech as I write. He’ll probably mention the fact that he was adopted and look how well he did, ignoring the irony that had he not been adopted into a middle class family, he almost certainly would not have achieved as he did.

The simple fact of the matter is that people whose experience has been wholly middle class are often utterly unable to understand the impact that deprivation has upon learning and achievement; they are similarly woefully ignorant about how difficult it is to teach children who don’t speak English fluently – because it’s extremely hard, extremely tiring and doesn’t always lend itself to a classful of A grades at GCSE, strangely enough.

At this point, I find myself having what I’m calling these days a ‘Boris Johnson’ moment – one of those times when you find yourself, against your very best judgment, supporting someone whose politics make you want to despise them. In Michael Wilshaw’s case it won’t last for long, but he recently spoke about how schools in areas of high deprivation ‘have to counter generations of failure and a culture which is often anti-school and anti-learning.’ I’ve no doubt, however, that Wilshaw will shortly issue another of his ‘If I were head of these schools every child would get As across the board and teachers must start trying harder or they’ll be flung off Beachy Head’ statements and I’ll be back to putting him at the very top of my ‘People I really, really don’t like and wouldn’t ask to join my gang or come to my house to play’ list.

I’m under no illusions that reading the results of this research will lead to any sort of Eureka moment in the two Michaels, but at this point, I’d like to pose a question and invite readers to post their suggestions in the comment spaces underneath this week’s piece. What does everyone think might be the reaction to this OECD research by Messrs Gove and Wilshaw – and will it in any way lead to even a tiny bit more respect for the teachers who work in such schools?

Please submit your comments below.

Helen Freeborn was a secondary headteacher for 11 years until she gave it all up to live in Greece. Now returned after four years abroad, she divides her time between consultancy, training, a range of writing projects and catching up with all the television she has missed.

More Posts

Share your expertise

Do you have something to say about this or any other school management issue which you'd like to share? Then write for us!

Share this article

16 Sep 2024 · News

How can we show we care?

16 Sep 2024 · News

How can we show we care?

5 Jul 2024 · News

Conscious Living, your Coach in your Pocket

5 Jul 2024 · News

Conscious Living, your Coach in your Pocket

6 Sep 2023 · Articles, News, Special Educational Needs

The Little Devil

6 Sep 2023 · Articles, News, Special Educational Needs

The Little Devil

25 May 2023 · Articles, Buildings and Grounds, News

Helping schools get the most out of heat pumps

25 May 2023 · Articles, Buildings and Grounds, News

Helping schools get the most out of heat pumps

25 Jan 2022 · News

Cost vs. Quality in the Purchasing of Air Purifiers For UK Schools

25 Jan 2022 · News

Cost vs. Quality in the Purchasing of Air Purifiers For UK Schools

11 Apr 2018

A Person — I am very concerned with the issues of children diet. It's important that kids get only nutritious food without any...

11 Apr 2018

A Person — I am very concerned with the issues of children diet. It's important that kids get only nutritious food without any...

3 Apr 2018

A Person — It will be released as an app in May 2018!

3 Apr 2018

A Person — It will be released as an app in May 2018!

19 Jul 2017

A Person — Great post, it really captures some great points! When children are playing outside, particularly during their time at school, it...

19 Jul 2017

A Person — Great post, it really captures some great points! When children are playing outside, particularly during their time at school, it...

25 Apr 2017

A Person — Canopies are a fantastic way of keeping the playground and other school grounds safe. Great article!

25 Apr 2017

A Person — Canopies are a fantastic way of keeping the playground and other school grounds safe. Great article!

2 Jan 2017

A Person — School management is the backbone of a school. Without management, an institution is absolute now.And school management software plays...

2 Jan 2017

A Person — School management is the backbone of a school. Without management, an institution is absolute now.And school management software plays...

Unhelpful Labels – OECD Education Report States the Bleedin’ Obvious

Posted by Helen Freeborn on 13 Sep 2012 in Comment · 0 Comments

Awaiting a fiery reaction from the St Michaels (Gove and Wilshaw, that is)

COMMENT – Have you noticed how most educational research, conducted by seemingly elite bodies and organisations, has a tendency to culminate in what Basil Fawlty would have described as a ‘statement of the bleedin’ obvious’? This was the very phrase which immediately sprang to mind when I read an article in the Telegraph of 11th September 2012, describing how research by the OECD showed that the ‘The UK’s school system is socially segregated, with immigrant children clustered in disadvantaged schools.’

Picking myself up from the ground to which I had collapsed in complete and utter shocked amazement, you can only imagine how astonished I was on reading further that the OECD had declared that this bit of research also showed that ‘the socio-economic make-up of the UK’s schools poses “significant challenges” for immigrant students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds.’

I wonder how they conducted this particular piece of ground-breaking research? Perhaps they popped into the pub nearest to a school serving one of our most deprived areas – let’s call it the Jeremy Kyle community college – at the end of last term and asked the beleaguered teaching staff whether or not they felt significantly challenged by their pupils. The researcher would, of course, have had to wait until the staff had unrolled their eyes before hearing them all declare ‘No! Every day is like teaching in fairyland. Even those children who live in houses where no-one’s ever worked and they’re only spoken to about once a fortnight arrive at school each day so ready and eager to learn it makes your heart swell.’

The researchers might then also have covered a school in an area where large numbers of immigrants from third world countries live – let’s call it Babel Academy. Perhaps they did a vox pop at the school gates, waiting hours for each exhausted teacher to emerge, blinking, into daylight from their ‘Building schools for the future’, artificially-lit buildings. And the questions asked might have included such gems as ‘What do you reckon – is it a little bit harder teaching in this place, where almost every child speaks English as their second language, where few have parents who speak much English and many of those parents are functionally illiterate in their mother tongue as well as English?’ If any of them had any strength left after spending all day, every day hurtling around their classrooms trying to assist large groups of children with the widest possible range of educational and linguistic needs, they might have aimed a feeble punch at their inquisitors.

I know what it’s like, because I taught for the first fifteen years of my career in four, extremely different London schools. The first was a good, ethnically varied all boys school in West London and so when I moved on to a school near Brick Lane, I could have been forgiven if I’d thought ‘A school full of nice Bangladeshi boys – they’ll be well behaved and studious, just like those middle class boys of Asian descent I’ve recently been teaching.’ The difference between the two experiences couldn’t have been greater and I’d got more than five years of teaching under my belt at this point – and league tables, targets and pressure beyond anyone’s wildest imagination were still on the DfE drawing board. It took me the whole of my first term to get over the shock of how many boys in each class I taught couldn’t speak English at all, as many were only recent immigrants to the UK, yet I was expected to teach them to GCSE level in the same class as a few boys who had been born in the UK and were completely bilingual. Many of the children at the school lived in squalor that had to be seen to be believed; accompanying pastoral colleagues on home visits sometimes brought me to tears, especially when parents would force us to sit and take food with them.

We’ve been here before, however. It will be only a matter of time – and I’ll bet that the usual suspect (naming no names, but he’s called Michael, is the secretary of state for education and has A level Smuggery) is preparing his ‘No excuses…children are being failed by crap teachers…the state sector must learn from the excellence of the private…etc’ speech as I write. He’ll probably mention the fact that he was adopted and look how well he did, ignoring the irony that had he not been adopted into a middle class family, he almost certainly would not have achieved as he did.

The simple fact of the matter is that people whose experience has been wholly middle class are often utterly unable to understand the impact that deprivation has upon learning and achievement; they are similarly woefully ignorant about how difficult it is to teach children who don’t speak English fluently – because it’s extremely hard, extremely tiring and doesn’t always lend itself to a classful of A grades at GCSE, strangely enough.

At this point, I find myself having what I’m calling these days a ‘Boris Johnson’ moment – one of those times when you find yourself, against your very best judgment, supporting someone whose politics make you want to despise them. In Michael Wilshaw’s case it won’t last for long, but he recently spoke about how schools in areas of high deprivation ‘have to counter generations of failure and a culture which is often anti-school and anti-learning.’ I’ve no doubt, however, that Wilshaw will shortly issue another of his ‘If I were head of these schools every child would get As across the board and teachers must start trying harder or they’ll be flung off Beachy Head’ statements and I’ll be back to putting him at the very top of my ‘People I really, really don’t like and wouldn’t ask to join my gang or come to my house to play’ list.

I’m under no illusions that reading the results of this research will lead to any sort of Eureka moment in the two Michaels, but at this point, I’d like to pose a question and invite readers to post their suggestions in the comment spaces underneath this week’s piece. What does everyone think might be the reaction to this OECD research by Messrs Gove and Wilshaw – and will it in any way lead to even a tiny bit more respect for the teachers who work in such schools?

Please submit your comments below.

Helen Freeborn

Helen Freeborn was a secondary headteacher for 11 years until she gave it all up to live in Greece. Now returned after four years abroad, she divides her time between consultancy, training, a range of writing projects and catching up with all the television she has missed.

More Posts

Do you have something to say about this or any other school management issue which you'd like to share? Then write for us!

Share this article